LOST YOUTH

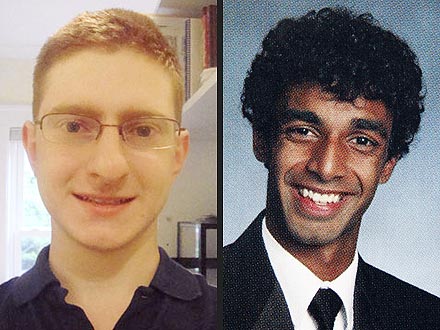

In the last ten days, the news has been overwhelming, both with the senseless murder of a young man in a hoodie and the legal case involving a young man with a violin and a young man accused of tormenting that young violinist due to his sexual orientation, resulting in his suicide. A waste of our beautiful young people.

Young men will be young men. Where are WE to protect them as they learn? Where are we as a society when we allow them to be brutalized?

Seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin wasn’t safe to go out for a bag of Skittles in his own neighborhood. Yes, George Zimmerman appears to be to blame for the actual death (as far as we can know from the news media versus actual evidence), and there are certainly questions about the speed of the investigation that followed. But what’s almost more disturbing is that Zimmerman was known to be a little too heavily into this vigilante mode, having many previous times called into the police about other “suspicious characters” he found on his self-appointed neighborhood patrols. Why wasn’t HE being watched? When Zimmerman called in with his report, he was told by the police NOT to follow Martin and not to take action—yet somehow he wasn’t charged or even investigated. Trayvon Martin was our son, our student, our future—left to the hands of some self-deputizing, gun-toting citizen—a bully, when you come right down to it. And nothing was done.

Over a year ago, a young gay musician at Rutgers named Tyler Clementi jumped off the George Washington Bridge, supposedly after being “outed” by his roommate, Dharun Ravi, who reportedly captured Tyler’s sexual encounters on his web cam and shared it with his friends. (The circumstances and what Rhavi did are now in question, despite the verdict—but more on that in a moment.) But the question is: what were the contributing factors? While Ravi’s drawing attention to Tyler’s private moments with an “older” man was no doubt one part of the equation, there are other things to be considered. Tyler had only recently come out to his parents, shortly before going off to Rutgers. No matter how wonderful his parents may be, there IS always a difficult period of adjustment when one proclaims oneself gay. It doesn’t make things better or worse, just different, and it takes time in a society where one’s sexuality apparently isn’t one’s own business. Add to that the actual “affair” that took place: a young gay man’s first tentative explorations can frequently lead one to an older partner who may be charming or have more experience but who may not be the best choice for a “relationship,” and in our first tentative searches, we look for Mr. Wonderful perhaps to help validate the realization of our sexual choice. Yet as with all searches for the right partner, it is less likely to happen right away and we make mistakes. The first mistakes hurt the most. It is possible that given his time away from home, his having recently come out to his folks, and his having perhaps been disappointed that this exploration was merely a tryst (and perhaps a disappointing one), Tyler may have been overwhelmed—and the additional unwanted spotlight may have just tipped him over the edge. Where are the counselors, the people who are supposed to help ANY youth, to guide them through these first tender, tentative forays into adulthood? Ravi’s point-and-perhaps-giggle may have shined a glaring spotlight on a sore spot, but there was much more no doubt going on. The search for the path to human connection is a painful one.

Finally, Dharun Ravi himself is a casualty, perhaps of short-sightedness, but he is not necessarily guilty of bullying. When I was a freshman (many many moons ago), my roommate had his girlfriend from another school down the hill up to the room and I was asked to become scarce. I was not pleased and I’m sure no doubt grumbled about it and made fun of him to my friends in a snarky fashion, as kids are wont to do. (We didn’t have the technology to spy, we didn’t have portable computers, and there was no Internet, Facebook or Twitter. But you can be sure that I griped to whoever would hear me.) Was I being heterophobic for complaining? If the word got out (due to me) that my roomie had slept with a girl and then committed suicide a few days later, would that be a hate crime case, a case of bullying? Surely, I would be accused of reacting stupidly and impulsively, but is that what these statutes were created to punish? According to Ravi, there was no recording or posting of the first sexual encounter, there was no publicized second encounter and there was no so-called viewing party, there were no images posted, just some grousing sarcastic comments. (Apparently, nothing presented at trial contradicts these claims.) And according to Ravi (in his NIGHTLINE interview with Chris Cuomo), the only reason anyone saw anything was because when the ticked off young man exiled on short notice from his room went across the hall, he was made enormously uncomfortable by the non-Rutgers “older” visitor in his dorm room and was just showing his female neighbor the strange-acting guy by quick-clicking his webcam on by remote—not expecting that mere moments later these two gents were already in action. (According to testimony from other students who were witnesses for the prosecution, Ravi’s reaction was surprise and shock, not one of malice.) And even as much as Ravi was Twittering about this, so was Clementi and they were reading each other’s Twitter feeds—while they would have done better to just talk directly to each other. There were no other “spying” episodes or recordings or posting of pictures, nor were any negative comments directed at Clementi. Was this an invasion of privacy? Absolutely. Was there stupidity in talking to others about it versus direct expression between roommates? Unquestionably. And was the ending tragic? Painfully. But was this an intentional hate crime, bullying? In an atmosphere where everyone’s raw and sensitive, in a constantly hostile world where it happens far too often on a daily basis . . . the line becomes harder to draw. Sentencing for the 15 counts will come up soon, but it is interesting to note that a) Ravi believes he did some stupid things and deserves to be punished, but b) he did not accept a plea bargain because he denies he did it out of bigotry or hatred and will not agree to a lesser term if he admits that bias and hatred was his motivation. So he may face up to ten years in prison and deportation for an act that contributed to a crisis but may not have been the key factor. (A suicide note in Tyler Clementi’s backpack was not made public at the trial.) Even outspoken anti-bullying critic Dan Savage (the “it gets better” campaign) seems to question whether justice is being served by making Ravi an object lesson.

Finally, Dharun Ravi himself is a casualty, perhaps of short-sightedness, but he is not necessarily guilty of bullying. When I was a freshman (many many moons ago), my roommate had his girlfriend from another school down the hill up to the room and I was asked to become scarce. I was not pleased and I’m sure no doubt grumbled about it and made fun of him to my friends in a snarky fashion, as kids are wont to do. (We didn’t have the technology to spy, we didn’t have portable computers, and there was no Internet, Facebook or Twitter. But you can be sure that I griped to whoever would hear me.) Was I being heterophobic for complaining? If the word got out (due to me) that my roomie had slept with a girl and then committed suicide a few days later, would that be a hate crime case, a case of bullying? Surely, I would be accused of reacting stupidly and impulsively, but is that what these statutes were created to punish? According to Ravi, there was no recording or posting of the first sexual encounter, there was no publicized second encounter and there was no so-called viewing party, there were no images posted, just some grousing sarcastic comments. (Apparently, nothing presented at trial contradicts these claims.) And according to Ravi (in his NIGHTLINE interview with Chris Cuomo), the only reason anyone saw anything was because when the ticked off young man exiled on short notice from his room went across the hall, he was made enormously uncomfortable by the non-Rutgers “older” visitor in his dorm room and was just showing his female neighbor the strange-acting guy by quick-clicking his webcam on by remote—not expecting that mere moments later these two gents were already in action. (According to testimony from other students who were witnesses for the prosecution, Ravi’s reaction was surprise and shock, not one of malice.) And even as much as Ravi was Twittering about this, so was Clementi and they were reading each other’s Twitter feeds—while they would have done better to just talk directly to each other. There were no other “spying” episodes or recordings or posting of pictures, nor were any negative comments directed at Clementi. Was this an invasion of privacy? Absolutely. Was there stupidity in talking to others about it versus direct expression between roommates? Unquestionably. And was the ending tragic? Painfully. But was this an intentional hate crime, bullying? In an atmosphere where everyone’s raw and sensitive, in a constantly hostile world where it happens far too often on a daily basis . . . the line becomes harder to draw. Sentencing for the 15 counts will come up soon, but it is interesting to note that a) Ravi believes he did some stupid things and deserves to be punished, but b) he did not accept a plea bargain because he denies he did it out of bigotry or hatred and will not agree to a lesser term if he admits that bias and hatred was his motivation. So he may face up to ten years in prison and deportation for an act that contributed to a crisis but may not have been the key factor. (A suicide note in Tyler Clementi’s backpack was not made public at the trial.) Even outspoken anti-bullying critic Dan Savage (the “it gets better” campaign) seems to question whether justice is being served by making Ravi an object lesson.

And so today I write to mourn the loss, the ruin of three young men whose biggest mistakes, perhaps, were their belief in their own safety, their own sense of invincibility, and their own inexperience. Where were WE as a people, with our experience and guidance? Do we not have an obligation to protect these young people, to teach them better judgment, to insure their basic safety and to protect their rights? We are quick to judge based on hearsay, rumor and early details—but should we be teaching people to take cooling off time, in this age of rapid electronic communication, before behaving rashly? Should we be teaching people how to protect themselves? Should we be teaching better communication skills? And when warning signs of danger occur, should we recognize them and warn the appropriate people? If so, perhaps Trayvon and Tyler would still be with us, and Dharun wouldn’t be sentenced to a ruined life based on what may have been a thoughtless prank.

No comments:

Post a Comment